Ludic

—a game we play—

– Children's Games, detail

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

Some say that Norbiton: Ideal City does not exist: it is merely a game we play, a Dungeons and Dragons of Norbiton acted out by a community of forlorn solitaries.

This is an understandable error. The Ideal City appears to be a game because it is rationally ordered. But you can walk its streets, drink in its pubs, eat in its restaurants, browse its invisible library and eavesdrop on the arcane business of its citizens. All real enough.

This is not to say that we do not play games, naturally associated as they are with stalemate and disqualification, bewilderment and capitulation, familiar enough ingredients of the Failed Life.

I am even sympathetic to the idea that the Ideal City might be experienced as a compendium of practices informed by a ludic disposition, practices which may or may not be games. The ludic impulse clearly underlies much that would not normally be recognised as game-playing—dancing, for example, or rioting, or thinking.

But a game, like a work of art, is a subset of the World: it is, in other words, only a game if there is a more extensive, less clearly structured World, part of which it models. The whole world can no more be a game than your life can be a work of art.

And, rumours of dragons and spattered knights roaming its drear hinterland notwithstanding, it is no longer clear to me where the Ideal City starts and ends.

—dragons and spattered knights—

– St. George and the Dragon, Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni

Vittore Carpaccio

![]()

In 1559 Pieter Bruegel painted a companion piece to his Battle of Carnival and Lent, a manic iteration of two hundred and fifteen children playing ninety different games in and around a market square.

—manic iteration—

– Children's Games

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

The games range from role playing games (a mock marriage, a mock baptism), through combative games (tug of war, the running of the gauntlet), games of chance (knucklebones and dice), games of athletic prowess (headstands, riding the fence, swinging on the bench, climbing trees, swimming) games of deception (blind man’s buff), games of skill (hoops, stilts), games of imaginative play (dolls, hobby horse), and games of generic rough and tumble. There are tops and coits and balls, a mock joust, some target practice, and follow-the-leader.

Unusually for Bruegel there is a strongly directed perspective scheme: a street to the right, a gradus ad parnassum, funnels attention towards a diaphanous church. But the goal is distant, if not actually illusory, and these children are not going anywhere. They are locked in their concentrated circuits of play, where all the material effects of this adultless town have undergone a transformation: the town hall becomes a play house, barrels and fences and benches are climbable obstacles or props, bricks are scraped for pigment, animal shit inspected for its ludic potential.

This improvisatory approach to the stuff of the world accords with something we know from our own experience, perhaps, rather than from the painting: that the rules of childish games are also Protean, volatile, omnidirectional; nothing stays the same for longer than necessary, rules are amended, codiciled, exceptioned, ad hoc, ad infinitum. Play is not a taxonomy of games each with a discrete rulebook; it is a mental space, an approach, a disposition. Release these children from their painted stasis, and they will whirl and collide, disband and reform, melt and coalesce: brisk, unpredictable, organised and anarchic.

![]()

Old Nestor Spinetto, blind Argentine coach of the reconstituted Norbiton FC, makes the same arguments about football. A football pitch, he suggests, is a properly ludic space, a space within which certain transformations occur: transformations which lead nowhere. On a football pitch you do not travel from Minute One to Minute Ninety. It is not ninety minutes cut from the ordinary cloth of your day, or of the spectators' day. No, the football pitch—or garden, or park, or beach—is a distinct plane of activity.

There is a ball, yes there is a ball; but there is, above all else, an occult disposition1.

It is, he says, like the dance (and he gives us a shimmy of a creaking tango with his shoulders, clicking his tongue): both are activities where at one and the same time you need to let yourself go and rein yourself in. And both are rituals—ritual sex or ritual fight. Society expects and demands that we both play and watch football in a given way, with a certain seriousness. Each game, it is clear, is a re-enactment of every other game ever played, from forgotten medieval village against forgotten medieval village, to the most hyper-ritualised cup-final. Seen from space, so to speak, they not only look identical: they are identical.

And seen from space, everyone can play football, just as everyone can fight, or copulate; just as everyone can dance.

![]()

I cannot dance, but I understand what he means. Dance is a version of play. Play has its communal rhythms, just as dance does. And dance has its transformative power.

In Book V of the Aeneid, the games held at the funeral of Anchises conclude with the youth of Troy performing a mock equestrian battle, more like a dance than a fight, in which three ranks of cavalry make feints and retreats ‘in beauteous order’, described in Dryden’s translation as follows:

And, as the Cretan Labyrinth of old,

With wand’ring Wave, and many a winding fold,

Involv’d the weary Feet, without redress,

In a round Error, which deny’d recess;

So fought the Trojan Boys in warlike Play,

Turn’d, and return’d, and still a diff’rent way.

Thus Dolphins, in the Deep, each other chase,

In Circles, when they swim around the wat’ry Race.

It is, we are to understand, an exuberant youthful exhibition, but also a structured one; and the key to the structure is the labyrinthine recursus, or return; the lines of horses advance and retreat, meet and wheel, engage and disengage, mimicking the steps of someone treading or in fact dancing a ceremonial labyrinth.

Virgil may in fact be alluding to a dance subsequently described by Plutarch who tells how, to mark the return of Theseus from Crete, the youth of Athens put on a celebratory dance which came to be known as the geranos2. The dance was still known at Delos in Plutarch’s day. It was a winding, involved, retrograde and meandering affair. Lines of choreographed youth would advance, break formation, and retrace their steps. And because they were trampling, so to speak, on the presumptions and tyranny of Minos and his beast, and were enacting the return of their king from the bowels of death, the renewal of all things, and regeneration in the face of death; because of all this, but perhaps most of all because they themselves were indisputably still alive and were dancing to prove it, it was a joyful whooping sort of a dance. A stomping celebratory ludic ecstasy. Dolphins and labyrinths.

The equestrian martial dance of Anchises’ funeral games serves a similar purpose. The youth of Troy are emblematic in their own persons of the refutation of Death. Anchises died and Troy fell, but these boys have sprung up like dragon teeth, ridden out armed and prepared, as alive as you get. And their funerary celebration, revived under Augustus and described by Virgil, will in time become a foundation myth.

![]()

If the evolutions of the Trojan funeral games are to be understood both as a dance and as a game, then they are a game in which chance elements have been substantially removed, or, similarly, a dance which has been thoroughly choreographed.

One of the chief ends of choreography is to eliminate or control chance. In the same way, games of the Renaissance, like games of all ages, are divided between those which seek to eliminate chance, and those which embrace it.

The two girls who are playing knucklebones in the lower left of Bruegel’s panel, for instance, have given themselves over to the dominion of chance events.

—dominion of chance events—

– Children's Games, knucklebones

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

Knucklebones—tali to the Romans, astragaloi to the Greeks—is played with the hocks or ankle-bones of sheep, which when tossed in the air can come down on one of four sides. The combinations of falling hocks can be scored in various ways.

As with dice or poker, chance in knucklebones could only be controlled by playing with the grain of probability. If you do not respect the probabilities, you will lose in the long run. Chance becomes the determining element. The player is bound to the wheel of chance outcomes, surrenders control.

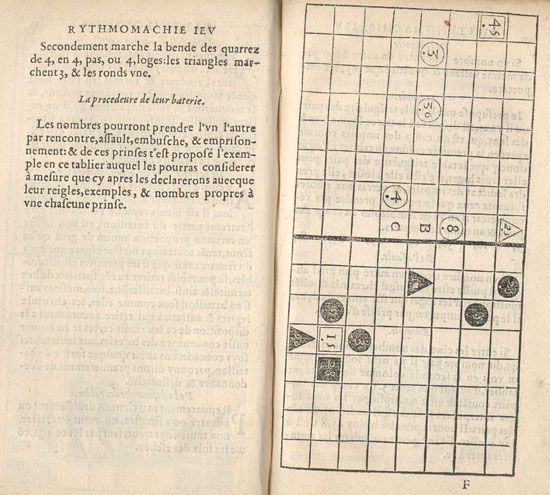

By contrast, the player of rithmomachia wrested control, not only of the game, but, in a necessarily limited way, of the Cosmos. Rithmomachia was a game of skill played on a chequered rectangular board with pieces numbered in sequences derived from Boethian number theory.

—talismanic affinities—

The object of the game varied depending on the ability of the players, but involved capturing opposing pieces and putting them to use to create significant patterns of numbers. And since the Renaissance cosmos was a numerical rather than a geometrical system, playing rithmomachia was a way of generating actual talismanic affinities, in the same way that Ficino would pluck mystical Pythagorean harmonies out of his lute, or arrange precious stones and roots of plants, in an attempt to divert the flow of the spiritus mundi in his direction.

Thus rithmomachia, partly a mnemonic and intellectual aid and partly the proper occupation of a magus or scholar, was bound intimately into its intellectual world. And for this reason, it was rapidly and almost entirely extinguished by the collapse of Boethian number theory, which was ousted by advances in trigonometry and algebra towards the end of the sixteenth century.

We do not exhaust the possibilities of games. The game merely ceases to be relevant. A game is an oblique form of inquiry, not simply an object of knowledge. And sooner or later we will cease to inquire into what no longer interests us, no matter how interesting the form of that inquiry.

Knucklebones and its cognates, it should be observed, remain a popular pastime.

![]()

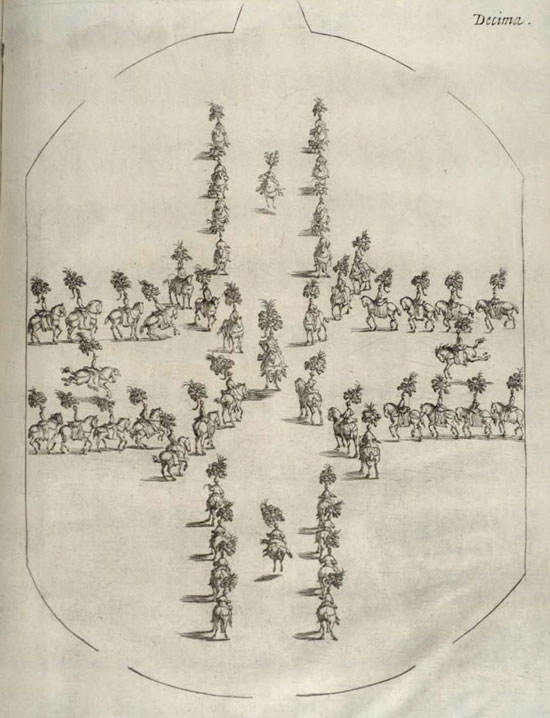

The Renaissance would have recognised the funeral games as an equestrian ballet, a preposterous art form itself suspended between the popular antiquarian tournament and the geometrical intricacies of courtly dance.

—preposterous art form—

– Choreography for a Rossballett, 1667, Vienna

Court dance was performed by courtiers, whose prowess in it was a matter of great pride. And not only physical pride: Lorenzo de’ Medici, for example, was a noted choreographer. To choreograph a dance, as to plant a garden, was to engage with cosmic geometries in a way that impacted on everyday life, because life, as Plato taught, was a dance that could be danced well: one of Plato’s terms for uncivilised is achorontes, or danceless.

By the late sixteenth century, court ballets and masques were designed as geometrically sophisticated entities to be watched from above, from a raised gallery. The steps performed were not complex, but the evolutions of the dancers were.

In 1573 at a series of Court entertainments under the auspices of Catherine de' Medici, and in honour of a delegation of visiting Poles (an event known thereafter as the ballet des polonaises), a dance performed by sixteen young ladies of the Court was described as follows by Pierre de Bourdeille, Seigneur de Brantôme:

"Elles vindrent marcher soubs l 'air de ces violons, et par une belle cadence, sans en sortir jamais, s'approcher et s'arrester un peu devant leurs Majestez, et puis après danser leur ballet si bizarrement invanté, et par tant de tours, contours et destours, d'entrelasseurs et meslanges, affrontemens et arrets, qu'aucune dame jamais ne faillit se trouver à son tour ny à son rang."3

The labyrinthine—hence liberating, redemptive—qualities of the dance were not accidental. It was a commonplace of court ballet and masque. To dance out the labyrinth, or to tread harmonious geometries, was to involve the body—both personal and communal—in a profound cosmic rhythmic play.

—tread harmonious geometries—

– Tapestry depicting a ball held by Catherine de' Medici at the Tuileries Palace, Paris, in 1573, in honour of visiting Polish envoys.

![]()

Nestor Spinetto, when I allude to the ballet des polonaises during the team talk before the game, nods in vigorous agreement. He says it is a commonplace that Italian stadiums, to take an example, steeple over the playing surface, so that the spectators look down on the tactical evolutions of the players from above. Italian play is patterned play. English stadiums are quite different. They are low to the ground, the spectators hard up against the field of play. English spectators feel the throb of adrenalin, but not the glow of intellectual satisfaction.

This, he says, is what he wants us to feel. We are not in a cage fight, but in a dance. We are footballers sub specie aeternitatis.

The Kingstonian XI, meanwhile, has been picked by Tony dell'Aquila, a director of Kingstonian. Tony was instrumental in that club’s takeover of Norbiton FC in the late 1980s and to judge from the team he selects, he feels no remorse. We are expecting an XI of ancients, beer-guts and wheezing rithmomatics to complement our own, but instead, it seems, he has emptied the gaols and the prison hulks. We are up against a tribe of rangy skinheads, rotten-toothed degenerates, foul-mouthed hod-carriers. The ball, when they smash it hilariously about in lieu of a warm up, is a hostile swerving unduckable scud of ordinance.

This is an empirically real football team. It is going to crucify us.

It has rained heavily in the days leading up to our match, and the going is very soft. There are a handful of actual spectators, Hunter Sidney and Tony dell'Aquila among them.

Nestor sits on the touchline, nodding like a philosopher, while in front of him the brutal mudbrawl unfolds; we are not tapping the chthonic energies of the game, or dancing for the pleasure of the gods; there is no pattern, just a white noise of football. In spite of Clarke's best efforts to martial us at the back, we are a porous unit, and we ship a goal every two minutes or so on average. After fifty minutes we are twenty-six goals to the bad, and everyone agrees enough is enough.

We have scored a single goal of our own, Konrad Moscicki's son Steve haring upfield in pursuit of a loose ball and stabbing it between the posts from a considerable distance. His father, who supplied the through ball, if you can call it that, lies on his back in the mud and roars encouragement. We give a weary and ironic cheer as it crosses the line.

When the game is over, Clarke is fuming but, to my surprise, Nestor seems satisfied.

He is in fact peculiarly charming about our woeful performance. He tells us, some games are not about winning or losing, or even participating; some games are not even about football. Some games are just about showing up, and keeping going. Keeping going. What else is there to do?

Football can be a properly melancholic pursuit.

![]()

What games do we play to prepare ourselves for death?

You might think, none. This is no time to restrict your liberty within some artificial structure; you have finally arrived in the place of pure seriousness, the point of completion, in which every aspect of your life is now laid out in its entirety: you have met everyone there was for you to meet; been everywhere you will ever go; listened very nearly to all the music and read all the books you will ever read; in short, you have now mustered all the data that will ever be available to you.

You cannot enjoy this moment, because naturally it coincides very nearly with your extinction. But in the weeks leading up to the moment, assuming you are not overly distracted by pain or fear, you might think, as I say, that it is no time for games: it is time for a great final contemplative effort.

But this is not true, because contemplation, no matter how powerfully you cudgel your brains, is no longer a route to transcendent Truth. Science has demonstrated that truth is not available to our unaided faculties, and even when we supply appropriate aids (Hadron colliders, radio telescopes, theoretical constructs of screaming complexity) since the tidbits of actual knowledge they throw up are wholly unintelligible.

The approach to death is thus merely another standpoint in life, and we do indeed play games; but directed to what end? I am not in a position to provide an exhaustive taxonomy, but I would imagine that there are Games of Deferral (we allow ourselves in various ways to believe that the end is not quite now; we have another day, another week; perhaps another season); Games of Quiescence (we find ways to convince ourselves that lines can be drawn, accounts closed, loose ends tied up); Games of Retribution (we confuse our fate with our enemies', our enemies with our allies, our allies with our fate, and strike out willy nilly). There are most probably games of Agony (death is a fight we can win), games of Piety (after death we will be docketed and processed for another state of being, and we need to pack one spiritual suitcase) and games of ludic despair (we make a display of irony, wit and resignation for the solace of our loved ones).

In short, there is one last mini-compendium of games, laid out for our amusement and pointless edification.

![]()

At a certain point in the course of our game of football I look up from the blur of mud and bodies towards the touchline, interested momentarily to see if Mrs Isobel Easter numbers among the spectators.

She does not. But I notice that Hunter Sidney has stood up from his camping chair, and has walked over to the fence separating our ground from the allotments, and is looking at the allotments. The next time I glance over, he is back in his chair. But I am strongly reminded of a painting by Bruegel—so much so, that in my moment of contemplation and to the disgust of a prone and swearing Civ Clarke, I let one of the Kingstonian skinheads through on goal.

This is the painting in question:

—mayhem of bodies...aggressive codpieces—

– The Wedding Dance

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

It is a wedding dance. What appears a mayhem of bodies rapidly resolves itself into a loosely but strongly organised geometry of arms and couples, a play of aggressive codpieces and concealing headscarves. This is still an orderly, if potentially seething, bacchanalia.

The dance is a group dance and exerts a gravitational pull, weak or strong, on everybody in the canvas, with the possible exception of one man—the solitary figure towards the very top of the painting, near the empty turf-cut benches and tables, with his back to the company and his hands behind his back; he stands there like one of Plato’s philosophers emerged from his cave and inspecting reality in the manner most habitual and comfortable to him: aurally, at a distance, sensing the presence of a sunlit world.

—emerged from his cave—

– The Wedding Dance, detail

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

There are other figures with their backs turned to the dance, but none quite so distinctly separate. The main axis of the painting runs from the viewer—standing no doubt in similarly contemplative mode—through the dance to the isolated man. He is like an iteration of the viewer. He views something after all, even if it is only the sixteenth century countryside equivalent of the cave wall—vanishing birds, fields, trees, perhaps the distant steeple of the next village.

There are two other oddities. A single man towards the rear of the dance as we look at it, is looking back out of the canvas at us, and appears in his astonishment to have seen us peering back in; and a shadowy half-figure, almost entirely lost in the trees, behind the pipers, is examining us as a woodland creature might, with a single eye, balancing the louche spectator in the red hat on the left, and the spectator in the fawn jerkin watching the musicians.

Bruegel is said to have disguised himself as a peasant and visited the kermises of various towns and villages, the better to observe his subjects. Perhaps he did not quite fit in as well as he would have wished, and found himself cannily inspected from time to time. Perhaps this inquisitorial glance was a commonplace of his experience.

However it may be, this painting is about the fringes of participation as much as the heart of it. Unsurprising, perhaps, that a painter should concern himself with the non-participants, the spectators. But if a dance, even a peasant dance, is, depending on your mood, a cosmic whorl, or a complex gravitational system of colliding and separating bodies, or an aggressive form of sexual play; then it is also necessarily a closed or semi-closed system; your participation is not guaranteed, however good your disguise; and at some point you will attend a dance to which you have been invited, and you will know that your dancing days are done, your exhilaration spent; and you will stand contemplating the allotments while others thrash about in a maelstrom of play, their whole combined endeavour merely a counter or token in your own difficult and arcane endgame, emblematic of your ludic dislocation.