Nocturnal

—no precise origin—

– Vision of Constantine before the Battle of the Milvian Bridge,

Piero della Franscesca

Night in Norbiton has no precise origin.

At a given time, darkness spreads in vaguely from the east, along the great creeping terminator of the self-shadow of the earth, reducing the city as it goes to an accidental heap of dwellings, shelters, pin pricks of camp fires, firefly populations.

But darkness and night are not identical. While the night is whatever it is—silent, numinous, depraved, terrifying—in virtue of the absence or diminution of ambient light, it does not precisely coincide with the coming and going of darkness.

And like all cities, Norbiton at night is never wholly dark. It is a jerry-rigged electric light show, an awkward cluster of variable noctilucence.

The Norbiton night is no simple object, then, no mere coagulation of darkness and slow time. For most inhabitants, it does not often happen at all. An individual will move from one brightly lit room to the next, then to bed, sleep (whether oblivious or insomniac), then to sudden full morning. The night was nothing more than a glitch in the ambitions of the day, an errance of the sun, a margin clapped shut between two tectonic spaces.

Thus the night in its proper form is something you must either feel out, or felicitously wake into. But once there you will find that whatever you might have aspired to be by day, by night you are a Failed Animal: isolated, immobile, vulnerable, but to a limited extent free.

—Failed Animal—

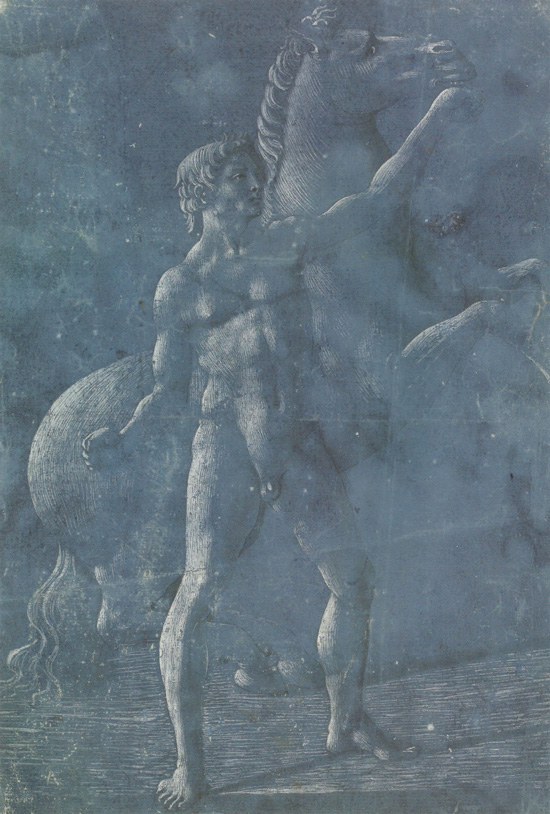

– A nude man with a horse (Dioscuri),

Benozzo Gozzoli

![]()

For a while in the early 1990s, after the collapse of his relationship with Isobel Easter and the departure of his family, Hunter Sidney (Decd.) took a six-month sabbatical from his work, and experimented with a twenty-six-hour cycle of sleep and waking. He would rigorously allot himself eight hours' sleep in each of his 'nights', but those hours of sleep would fall two hours later each day, so that he and the night, itself of variable length, orbited one another like dark binary stars.

In this period he rarely left his empty house. He was working on a novel (unpublished) at the time —these were the days before the Internet, before the anti-literature—and he enjoyed the slight lag and drag, the imperious slowness of his long days.

But a problem emerged. Whatever he wrote at night—real night, the dark nighttime—always exhibited, when read back in the daylight, a grotesqueness, an indulgence, a rabid quality, as though he were routinely possessed in the dark watches by a garrulous hallucinating maniac.

Deep night, he was learning, induces a range of psycho-perceptual changes associated with increased vigilance, awareness. By night, we are a predated species. There are monsters beyond the ring of firelight, and we scribble and jibber accordingly.

One night, towards the end of the period, he woke at his allotted time in the dark of actual night, and caught a momentary vision of himself sitting in an armchair on the far side of the room, placidly looking back at him. He rubbed his eyes and the vision was gone. But he reverted from that moment to a twenty-four-hour cycle, not out of fear, but out of pragmatism. The night, he now knew, must be treated as a wholly different entity.

![]()

To repeat, while the night is broadly characterised by darkness, night and darkness are not the same thing. Night is an object of the mind, it has a history.

In the early centuries of the Christian era, for instance, the night was opened up by the monastic offices, specifically nocturns, sometimes known as matins or vigils, the longest and most involved of the offices which ran from about two in the morning to shortly before first light.

The darkness of night, to the sleep-deprived early monk, was an analogue of the pre-creational chaos; their psalmody—the settings of the psalms of David—was in consequence spun from that chaos, a songlines of melismatic creation. The night was articulated, given shape, through the hypnotic and endless, but not self-same repetition of the psalms.

Those early chapels, we are to understand, were places of aural contemplation. Contemplation properly understood is contemplation of a thing—usually a thing placed before the eyes. But the chapels during nocturns were dark, and the only objects of attention were the bodily discomfort of the monk and the well-worn sound of the chant, the antiphons and responses of the office.

It has been postulated that the mind, released from the performance of tasks requiring predominantly visual input and control (such as, for example, work), will revert to a discrete sub-system of functional areas (known as the task-negative network) associated with imagination and memory, where we are most in possession of our complex selves. Monks, we might speculatively conclude, forged their monkish souls in the slow production and embellishment of ornamental lines of song spinning through the cold stone chapels in the watches of the night, like strings of code, as it might be, for all Western Civilisation.

![]()

Sometimes I fail to sleep. Clarke slumbers heavily on my sofa each night, so I go down into the streets of Norbiton and take a walk.

This is not insomnia. Insomnia belongs to the day, is a debt owed to the diurnal world, and is accordingly characterised by a shambles of mind.

—insomnia belongs to the day—

– In My Bed,

John Kirby

Without the pressure of daily routines and obligations, there is no constraint on patterns of sleep; your sleep is at liberty to spill out over the plains of your life, filling low lying pockets of time with its drowsy sediment.

This wakefulness is not insomnia, then, but it borrows from insomnia its febrile acuity, as though scouting out the motions of your soul required a nocturnal sensibility. Thus it is that, so many hypervigilant arboreals, we have learnt to navigate in Norbiton by the minor lights—moon, stars, lamps, the belch of marsh gas over the sewage works on Marsh lane; the fizz of low pressure sodium, security halogen, light emitting diode—which cast in their criss-cross way an approximate, delicate system of intersecting lines, faint terminators.

What to the insomniac reads as a grotesquely-scaled despair, to the nocturnal—if I may so style the diaspora of the Failed City—translates into a logarithmic and readable code. By night, in other words, up and moving and awake, navigating by the minor lights, we are able to read off the logic of the program that by day we run, unthinking.

—read off the logic of the program—

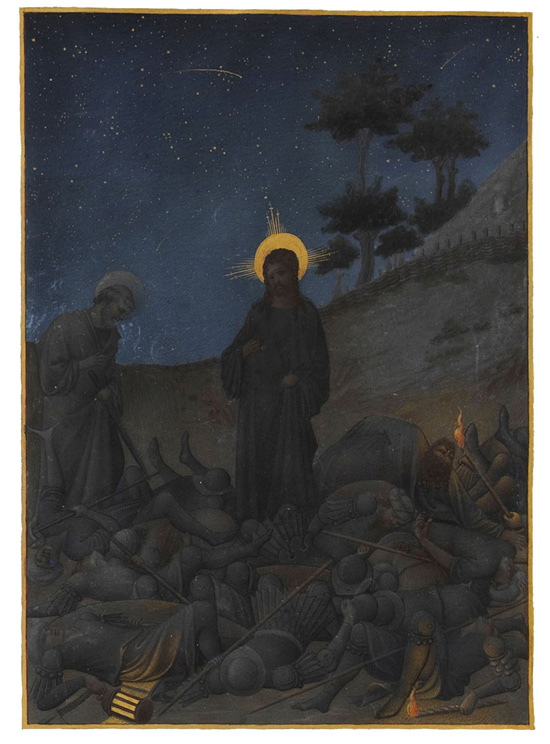

– Christ in Gethsemene,

Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry, Limbourg Brothers

![]()

On one such night-excursion, near dawn, I encounter Kelley out walking with his dogs. I am just coming down to the bottom of Manorgate Road, and he is crossing the far side of the roundabout on the London Road, coming down the hill. He is only taking his dogs for a walk in the early morning, but for me this is still night time, I am still preternaturally alert, and so I see him as a ghost of himself, a Faustian relic of the night, an Orion detached from the sky, trailing sulphurous fumes and emblematic dogs, as though he had pulled himself out from under the dead weight of the sleeping city and was newly pleased with the elasticity of his limbs.

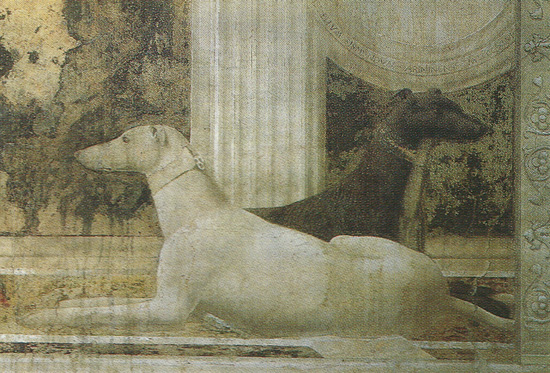

—emblematic dogs—

– Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta Praying Before St. Sigismond,

Piero della Francesca

Which is to say, I am momentarily scared that he will see me, and I freeze until he has gone past.

![]()

There is very little night in the Italian Renaissance: it is a peculiarly daylit world.

It is, however, a daylit world laced with a nocturnal sensibility, populated with singular night-visions: angels visiting virgins in broad daylight; saints with their peculiar attributes—eyes on plates, axes in heads—assembling in honour of a capricious infant god; or Ovidian transformations, mutable forms, human to bird, human to tree, human to lynx and dolphin.

The stuff of night in the Renaissance is flushed egregiously, but very naturally, into the day; its daylit world is a dreamscape of odd clarity.

—odd clarity—

– Birth of the Virgin,

Fra Carnevale

![]()

In Piero della Francesca's Vision of Constantine before the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in the church of San Francesco in Arezzo, where a night scene is clearly demanded by the logic of the narrative, the night sky is leavened to a pre-dawn glimmer.

—pre-dawn glimmer—

– Dream of Constantine,

Piero della Francesca

Agnolo Gaddi, who painted the prototype for Piero’s cycle in the choir of Santa Croce towards the end of the 1380s, made this particular scene properly dark—the vision is night-spectral, rather than morning-inspired, the wild-horsed emperor emerging from the side of the tent like Athena sprung from the head of Zeus, the impending battle a vision of madness, or a mad continuation of the vision.

—night-spectral—

– Dream of Constantine,

Agnolo Gaddi

Piero, in picking up Gaddi’s composition, inverts it in a number of ways. In the Gaddi, the Emperor is awake while his retainers sleep; in the Piero, the retainers are caught in the sudden illumination of the angelic visit like unblinking nocturnal creatures, as though it is they and not the angel who constitute the Emperor’s strange vision.

Then, Piero’s tents are silhouetted where Gaddi’s are fully modelled—Piero is alive to the precise directionality of light in a way that Gaddi, for whatever reason, is not. Gaddi has painted his tents as though objects in the world were fully themselves regardless of how they might be lit; he has struck them off some block of thinghood and set them down in the night, things and the night being distinct and immiscible categories.

For Piero, meanwhile, an object in the dark is an object without clear edges, definition, or saturated colour; in the night, thing bleeds into thing, and what small light there is accords each separate thing, each separate self, just so much existence that it can be known without obliterating every other thing, every other self. His nocturnal world is one articulated by low and clearly directional lights, lights which delicately—hence precisely—feel out and map an insubstantial phenomenal world.

![]()

A few nights after my encounter with Kelley, when I am about to go out again, I find that Clarke is awake and restless, so I tell him about Kelley and his spectral dogs, out owning the night. He leans up on one elbow, and relates the following story.

In the early 1990s, when his wife was grappling with the onset of her agoraphobia, Ted Kelley occupied his own sleepless nights building a treehouse in Richmond Park.

He seems to have reasoned that his wife’s agoraphobia was a function of crowds and daylight, an analogue to his own insomnia. So he smuggled over his materials night after night, planks and spars and rope, nails and screws, blankets and candles, and hoisted them somehow up to the high branches of his chosen tree.

For a couple of months that summer he and his wife would make frequent surreptitious nightly trips to the park, scale the walls, dodge the foresters, climb up into their treehouse, and enjoy the benign nocturnal space.

It was a space, according to Clarke’s supposition, in which Kelley sought to unperplex his own putative guilt. Kelley was in some way responsible for his wife’s monastic retreat—so goes the Clarke theory—and both the tree house and the night itself were presented as a sort of atonement, a medieval balm of sympathies.

In fact, he was only replacing one schizoid space with another. A tree house is the schizoid retreat par excellence. There was nothing to be achieved up there by Kelley and his wife, no cure to be had. And perhaps that in itself was the point. The treehouse was a dissociated, imbecile gesture, a small known space in the forlorn immensity of Richmond Park.

Anyway, with autumn the leaves came off the trees, and the treehouse was discovered and dismantled. Kelley and his wife descended into less adventurous patterns of anxiety management.

If the Ideal City were still a burgeoning metropolis, and not the barbarian ravaged dilapidation that it has become, I like to think we would project to rebuild the tree house. We might seek to winkle Mrs Isobel Easter—as I call Mrs Kelley—from her studiolo, harness Kelley on his night walk, and mount watchful silent invisible guard in the forests while they drank wine in the trees.

But Clarke, his story told, snores heavily on my sofa, and Hunter Sidney and Cannoner are dead; Old Sol and Emmet Lloyd's tree-climbing days are behind them, and Veronica de Viggiani has gone back to Rome; and I am no dryad.

![]()

While the painters of the Italian Renaissance were content to explore the diurnal system of space and light which with such persistent inquiry over a century and a half they had carved out, in the North it was somewhat different.

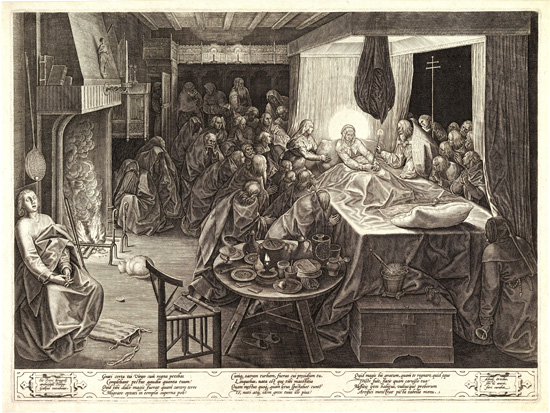

In around 1564, Pieter Bruegel painted for his friend, the great Antwerp geographer and humanist Abraham Ortelius (who would, in the year after Bruegel’s death, publish the first atlas of the world, the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum) a small grisaille Dormition of the Virgin, his own modest contribution to an atlas of the long night.

—atlas of the long night—

– Dormition of the Virgin,

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

This is properly night: a night constructed, first, by a general blanching of colour—it is painted on a yellow ground, predominantly in greys, with occasional warmer browns; and, secondly, by the establishment of a simple network of light-sources, four in number—the fire in the grate, the candle on the foreground table, the pair of lights above the door, and the halo-candle complex—which, like Wallace Stevens’ fishing boats1, serve to analyse and shape the night.

There is no ambient light. All light can be traced to one or other source, and—with one exception, the Virgin’s halo, which is rendered as pure light—each is itself near-swamped by the darkness. Darkness is a thing, and it is in the calibration of that darkness that the composition is worked out, especially since the dominant light source—the Virgin—is anyway about to be extinguished, and nothing else will hold out against the darkness.

Five years after Bruegel’s death, in 1574, Ortelius had an engraving made of the Dormition by Phillips Galle, which he then distributed to friends and acquaintances.

The prints of the engraving (done in reverse to maintain the spatial orientation) are also monochrome, but the gradations of shading and shadowing, standing conventionally for daylight hues, have brought the crowd around the bed tumbling out of the shadows. What in the original had been a thick paste of darkness, pregnant with unformed individuals considered only as a mass or presence, in the engraving is a compaction of individuated and particulate bodies, exhausting the composition, resolving ambiguities.

—compaction of individuated and particulate bodies—

– Dormition of the Virgin,

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, engraving by Phillips Galle

Moreover, the space is now fully constructed. In Bruegel’s original, there was no landscape or architecture. The actors in his scene cannot be located, except in vague relation one to the other—the cat to the virgin to the sleeping Evangelist—all are floating in some social, spatial, cosmic dissociation.

It is this quality of dissociation, separation and subsequent definition which characterises nocturnal objects.

![]()

Darkness, like the Norbiton Night, has no precise origin.

Light can be traced to a source—a charged filament, a luminescent gas, a bio-chemical process. But dark is not a thing. It is an absence, a perpetual draining of the cold container of space. It comes—if we want to be precise—from nowhere, wrong-footing in the process the grammar of our language and of our imaginations, both of which are built on a presumption of presence, of agency, of things that are and do.

Little wonder than that by night in Norbiton we are ungrammatical beings, gibbering to ourselves in our private mental argots. At the beginning of Act IV of Le Nozze di Figaro, as the farce approaches its febrile climax, a character called Barbarina is searching for a pin she has lost. She sings an inconclusive lament. The pin was a love offering of the Count to Susanna, Figaro's bride-to-be, and Barbarina will be in trouble.

But the pin is a red herring, a mystifying detail whose origin or significance no audience can ever really recall. It is an emblem merely, a floating sign of imbroglio. The pin is lost in the darkness of the garden, a stray sheered object rattling in the melancholy machinery of the night. Nothing is any longer connected to anything, there is no underpinning logic.

The remedy to this general confusion, this dispersal of bodies through the garden, is not more plot, more linking of events (although there is plenty of that), but less. At a certain arbitrary point, all dissimulation falls away, and the Count, nominal root of the problem, is left to ask his wife for forgiveness, which she grants. And while the resolution seems trite, Mozart knows that it is not.

The forgiveness that the Count asks is not part of a precise audit, or reckoning; he and the Countess, in the garden at night, are momentarily no longer caught in the judicial logic of transgression, offence, recrimination. The action of forgiveness—both asking and granting—is a more general, more melancholic acknowledgement of a mutual state of things; it references a plane of sorrow that is universal.

![]()

Some have suggested that those early monks in their nocturnal offices were preparing for the advent of day2. The point of the night, it was supposed, was that day would come, resolving the paradox that a community obsessed with supernatural light (lux) should relegate its most involved rituals of prayer to the middle of the night.

But this is not so. The basis of early monastic life was a wholesale nocturnal sensibility of dissociation and contemplation, regardless of the hour of day. Just as Mozart’s Count and Countess are able to access a universal, little-visited plane—whether of sorrow, of comity or simply of understanding—so the nocturnal plane lies around us, mostly unexpressed, at all times.

The objects of night are not connected by causation, narrative, or events, but by a unifying sensibility. At night each thing floats in empty space, picked out and given shape by the cross-lights of thought, like a green-blue planet caught in a fleck of light to the eye of a passing god3.

There are no gods, only us. Yet while the ideal city of the Failed Life may have crumbed, may lie in bleached and buried ruins against which the thunderstruck ploughs of future generations will run up, the vestigial Failed Life remains. We are not monks, now, but scattered friars, remembering in isolation the offices we once kept.